Timberland Shoes Outlet Sale 60% Off Summer

Cheap timberland shoes

Store News

Timberland Boots Outlet Not Entitled to Trademark Protection

As it turns out, advertising the same product for more than three decades does not guarantee a trademark registration on its design. Timberland learned this after the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB) affirmed the rejection of Timberland’s product design trade dress application for its iconic work boots. See In re: TBL Licensing, LLC, No. 86634819 (Apr. 2, 2021).

The Mark

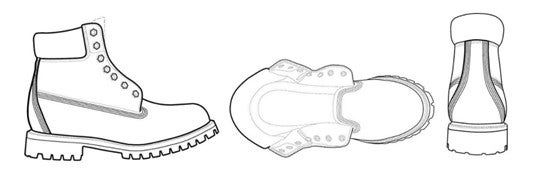

In 2015, Timberland filed a trademark application for “lace-up boots,†consisting of a three-dimensional configuration having the following features:

-

Silhouette: The overall silhouette of the boot features a bulbous appearance in the toe cavity area;

-

Collar Profile: The ankle collar frames padding on the outside of the boot;

-

Lug Sole Design: The boot displays a lug design on the exterior side of the outsole;

-

Two-Toned Outsole: The outsole features two perceptively differing color tones, distinguishing an upper and a lower portion of the outsole;

-

Hourglass Rear Heel Shape: The rear of the boot features an hourglass-shaped rear heel material;

-

Stitching: Four parallel rows of stitching adorn the outside material and form an inverted “U†shape around the vamp line on the front of the boot, and also are displayed to define the rear hourglass heel shape; and

-

Hexagonal Eyelets: The shoelace eyelets are hexagonally shaped on the outside.

Application No. 86634819 (May 19, 2015). The applied-for mark is depicted by the figures below, where the solid lines delineate the claimed attributes of the mark:

Application No. 86634819 at Drawings (May 19, 2015). The application listed Dec. 1, 1988, as the date of first use.

The Rejection

The application was ultimately rejected on the grounds that, inter alia, (1) the proposed mark is a product configuration comprising non-distinctive features for which the evidence of acquired distinctiveness is insufficient; and (2) the proposed mark comprises functional trade dress. After Timberland’s request for reconsideration was denied, the TTAB heard the appeal and affirmed the Examiner in an opinion issued April 2, 2021.

TTAB’s Opinion

Because product design is never inherently distinctive, the TTAB considered whether the applied-for non-distinctive product design had acquired distinctiveness. Wal-Mart Stores Inc. v. Samara Bros. Inc., 529 U.S. 205, 54 USPQ2d 1065, 1068 (2000). The TTAB focused the inquiry on whether any purported acquired distinctiveness related to the promotion and recognition of the specific configuration embodied in the proposed mark, rather than to the goods generally.

The TTAB’s analysis followed the relevant Converse factors: (1) association of the trademark with a particular source by actual purchasers, (2) length and exclusivity of use, (3) amount and manner of advertising; (4) amount of sales and number of customers, (5) intentional copying, and (6) unsolicited media coverage of the product embodying the mark. Converse, Inc. v. Int’l Trade Comm’n, 907 F.3d 1361, 128 USPQ2d 1538, 1546 (Fed. Cir. 2018).

(a) Association of the Trademark With a Particular Source By Actual Purchasers

Typically, direct consumer testimony or market surveys provide the most beneficial evidence regarding consumer perception of a mark. Timberland proffered neither. Instead, Timberland put forth two declarations from its own retailers which purported to show the acquired distinctiveness of the boot generally, without specifically mentioning the appeal of any of the applied-for features. The TTAB found that those declarations were of “little probative value†and noted that the retailers are not “average†consumers of the boot. The TTAB cited In re Semel for the proposition that assertions of retailers cannot be said to be representative of the consuming public due to their specialized knowledge. 189 USPQ 285, 288 (TTAB 1975).

The TTAB also discredited Timberland’s many examples of celebrities like Justin Bieber, Rihanna, and Jay-Z (or his daughter, Blue Ivy Carter) wearing boots that embodied the claimed trade dress. According to the TTAB, the evidence merely demonstrated the popularity of the boots, but the Board stressed that popularity does not equate to a showing that the celebrities associated the claimed trade dress with Timberland. The photos also did not draw the attention of potential customers to the claimed trade dress (i.e., the shape, stitching, rear heel shape).

(b) Length and Exclusivity of Use

Timberland has been in business since 1973 and began use of the claimed two-toned outsole in 1988. The TTAB did not credit the length of use, finding instead that the record showed a lack of substantially exclusive use of the alleged trade dress. Timberland pointed to various copycat boots designed over the decades as evidence that the design of the boot was popular. According to Timberland’s employees, these copies were all unauthorized. The TTAB found that this evidence actually weighed against Timberland’s case.

First, the evidence showed that the overall silhouette and appearance of the claimed boot was common in the industry, rather than “substantially exclusive†to Timberland. Second, and more importantly, the TTAB found that Timberland did a poor job of policing its product design, because despite the numerous “unauthorized†copies of the boot that existed, Timberland asserted its purported trade dress rights only once. The inaction, coupled with evidence of third-party use, led the TTAB to conclude that Timberland failed to meet the “substantially exclusive†prong required by 15 U.S.C. § 1052(f).

(c) Advertising Factors: Amount and Manner of Advertising; Amount of Sales and Number of Customers; and Unsolicited Media Coverage of the Product Embodying the Mark

Timberland earned $1.3 billion in revenue from the boot (and spent $1.5 million on advertising) in the last 15 years. However, the TTAB found that successful product sales are “not probative of purchaser recognition of configuration as an indication of source.†To determine whether the impressive sales were caused by the applied-for trade dress components embodied within the shoe, the TTAB evaluated Timberland’s advertisements, none of which highlighted any of the claimed components. Rather, the advertisements always pictured or highlighted the general style, tree logo, and yellow color of the boot, none of which were claimed in the application.

Timberland argued that this amounted to a rejection for lack of “look-for†advertisements. The Examiner conceded that look-for advertising is not always necessary, and that what matters is the consuming public’s recognition of the trade dress as a source indicator. Either way, the TTAB found the evidence did not show that any of the claimed trade dress components served as source identifiers, due to their ubiquity in the boot industry. The TTAB also noted that the only feature of the boot that arguably served as a source indicator was the tree design logo used in advertisements. Indeed, one of the articles cited by Timberland stated that the Timberland tree logo burned into the side of the Timberland boot is what “made the boot an icon.â€

(d) Intentional Copying

As discussed in greater detail above, Timberland presented several examples of “copied†boots to support its argument. However, Timberland did not proffer any evidence to show that the third-party boots were made for the purpose of passing-off or creating consumer confusion. This was clear because the third-party boot images clearly displayed the manufacturer’s, not Timberland’s, name and logo on the boots or in the advertisements submitted by Timberland.

Lessons Learned from Timberland

(a) Police Your Mark!

Timberland’s substantial evidence of purported “unauthorized†copying worked to its detriment due to its repeated failure to police the claimed trade dress. It is critical not only to monitor official filings (for example, pending and published applications) but also to keep tabs on the market and products for sale. A potential plaintiff’s failure to enforce its mark against potential infringers can be fatal to a future claim of infringement in a court or, in this case, claims of substantial exclusivity necessary to secure a registration at the USPTO.

(b) Be Mindful of Your Advertising Style

The TTAB made clear in its opinion that “look-for†advertising is not mandated. In fact, a company is free to advertise its goods and services as it sees fit, so long as that advertising conveys the elements of any potential trademarks. But the discussion of the absence of “look-for†advertising illustrates how compelling such advertising can be. Timberland may have benefitted from advertising its boots in a way that distinguished them from the conventional work boot by highlighting the various shapes and silhouettes that make up the boot, thereby emphasizing the particular design features claimed in the application. Meanwhile, simply relying upon celebrity sightings to establish consumer recognition of the claimed design features may not succeed. The TTAB thus distinguished between evidence of the boot’s general popularity (not probative) and consumer association of the claimed design features with Timberland as the source of the boots (probative).

(c) Always Get the Consumer’s Perspective

Timberland’s evidence of acquired distinctiveness focused primarily on the declarations of two of its own retailers and their characterizations of the marks and the consumer market. This was fatal to Timberland’s case. Acquired distinctiveness is determined from the perspective of the consuming public – trademark law is, primarily, a consumer protection body of law – and not by those with specialized knowledge, such as store owners, retail buyers, or shoe company executives. Consumer surveys may be expensive and complicated, but when they show conclusive evidence about the public’s perception of a mark, surveys can often make or break a case.

News for Sunday 18 April, 2021

View all news for Sunday 18 April, 2021 on one page

Recent News

- Friday 26 March, 2021

- Friday 12 February, 2021

- Tuesday 09 February, 2021

- Tuesday 09 February, 2021

- Wednesday 03 February, 2021

Follow us